How to calculate and reduce payback period

How much revenue is a good amount of revenue? One answer is when it is more than you spent generating it. In other words, when it turns from revenue into profit.

The time it takes for a customer to become profitable (or break even) is known as the payback period. In this guide, we’ll unpack why the payback period is important for SaaS businesses, how to calculate it and (most importantly) how to reduce it.

What is a payback period and why is it important?

A payback period is the time it takes for a customer to become profitable (or break even). Payback period is a fundamental SaaS metric, as it contextualizes customer numbers. For example, your customer numbers could be rocketing; but if you’re spending too much money acquiring them, it might take a long time before they pay back that investment. It works the other way too. At first glance customer growth may seem sluggish. But if that is letting you control costs, and so customers are turning a profit more quickly, it can be seen as a positive.

Payback period is important to all SaaS businesses as it directly impacts cash flow. A long payback period will negatively impact cash flow, and reducing it will improve how much money you have to play with. It follows that the tighter your cash flow, the more emphasis you will place on the payback period. This is the case for startups, especially those at pre or early stage funding, where they are as reliant on their customer’s money as their investors’. So too SaaS businesses that operate tight margins, and so where fluctuating payback periods have a more profound impact. Businesses that expect a high turnover of customers (e.g. they have a low cost, non-critical product in a highly competitive market) will also prioritize turning a profit fast.

More established SaaS businesses may not put the same emphasis on payback period. For starters, they will have retained earnings to fall back on; and they should have a more predictable cash flow from a longer-serving customer base. But that’s not to say payback period should be ignored. Payback period is a forerunner of long-term profitability, so regularly tracking it will alert you to things going wrong, in time for you to put them right. And if you are readying your business for a new round of investment or a sale, a healthy payback period will be a key metric determining value.

How to calculate payback period

The basic calculation for payback period is simple - just divide the cost of acquiring a customer by the revenue they generate over a period of time.

Example

It costs $100 to acquire a customer. Their subscription is worth $10 per month. So in 10 months they will have generated enough revenue to cover the cost of their acquisition.

$100 / $10 per month = 10 months

Payback period does not always have to be measured in months. For some SaaS businesses, with longer customer acquisition and lifecycle terms, it may make more sense to measure payback period in quarters or even years.

Example

It costs $5,000 to acquire a customer. They pay $250 quarterly. So it will take 20 quarters, or 5 years, to generate enough revenue to cover the cost of acquisition.

$5,000 / $250 per quarter = 20 quarters

Issues with calculating payback period and how to overcome them

Critics of the payback period metric will level a range of charges at its door. Here we look at some of them, and how to adjust your calculations accordingly.

1. It is too general

Typically, payback period is calculated across a whole business, by totaling all customer acquisition costs in a period, and dividing by revenue contributed by new customers for the following period.

For example, if marketing costs for January were $18,000 and revenue generated by new customers in February was $2,000. It will take those new customers 9 months to cover the cost of their acquisition.

$18,000 / $2,000 = 9 months

But this doesn’t tell you enough. For example, there may be some marketing channels that produce more profitable customers, faster. You’ll want to double-down on these. Or you may have extremes of customers - from those who join at a heavily discounted price, to those who cost relatively more but that are likely to stay for longer. By aggregating them all together, you can skew the calculation and get a misleading measurement.

How to overcome: The answer is to segment your costs and customers, according to what makes sense to your business.

2. It doesn’t account for churn

Using the example above, what happens if some of those new customers churn before 9 months? The cost of acquisition has already been sunk and so will remain the same, but the revenue side of the equation will be reduced. As a result, the payback period will increase; but for customers who remain, the payback period will have been unaffected (all other things being equal).

How to overcome: One approach is to strip out customers who churn and calculate the loss from them separately.

3. It presumes ongoing profitability

It becomes more misleading when customers churn or downgrade after their payback period. The payback period presumes that once customers become profitable, they stay profitable - but SaaS businesses know that is far from reality.

How to overcome: The answer is to be clear about what payback period is illustrating, and not be tempted to use it to make long term revenue and profit projections.

4. It ignores upgrades (sometimes)

What type of revenue you include makes a difference to the payback period. If you only count revenue from the initial subscription and miss extra revenue from upgrades or price increases generated during the payback period, then you’ll be understating the payback period. And at what moment do you stop recognizing new revenue - at the exact point a customer reaches their acquisition cost (to the dollar and cents), or do you include everything in the time period you are measuring?

How to overcome: The answer is to have clear definitions in place of how you are going to define revenue for the purposes of calculating payback period; and the analytical systems that allow you to pull the data accurately.

5. What counts as a cost?

Some acquisition costs are obvious, such as advertising and marketing spend. Some are less so - for example press coverage, hackathon events and how you support your current customers all feed into your brand reputation. In theory, payback period should include all customer acquisition costs, not just the direct ones. But attributing an activity to a customer acquisition is easier said than done.

How to overcome: Though accuracy is important, consistency is more so as it allows you to compare payback period over time.

6. It is ambiguous about who to include

You need to be clear about what constitutes a new customer. Is it fair to include extra users in existing accounts, where there may have been very little, if any, acquisition cost? Also should you treat the cost and revenue of returning customers in the same way as brand new ones?

How to overcome: Again, the answer is to have clear definitions in place, to ensure you are measuring payback period consistently.

7. It does not account for inflation

As payback period measures cost of acquisition at a specific moment in time, that part of the calculation can be skewed by inflation. In other words, $10 last year is not worth the same as $10 this year. The problem is more profound when calculating payback over longer periods; and more so if you regularly adjust your prices for inflation.

How to overcome: The answer is to adjust the cost of acquisition in your analysis, so it remains relative.

As we have read, there can be different ways to measure payback period, and therefore different benchmarks. Payback period also faces the same benchmarking challenge as other SaaS metrics, in that it can vary across different sectors, business models and geographies.

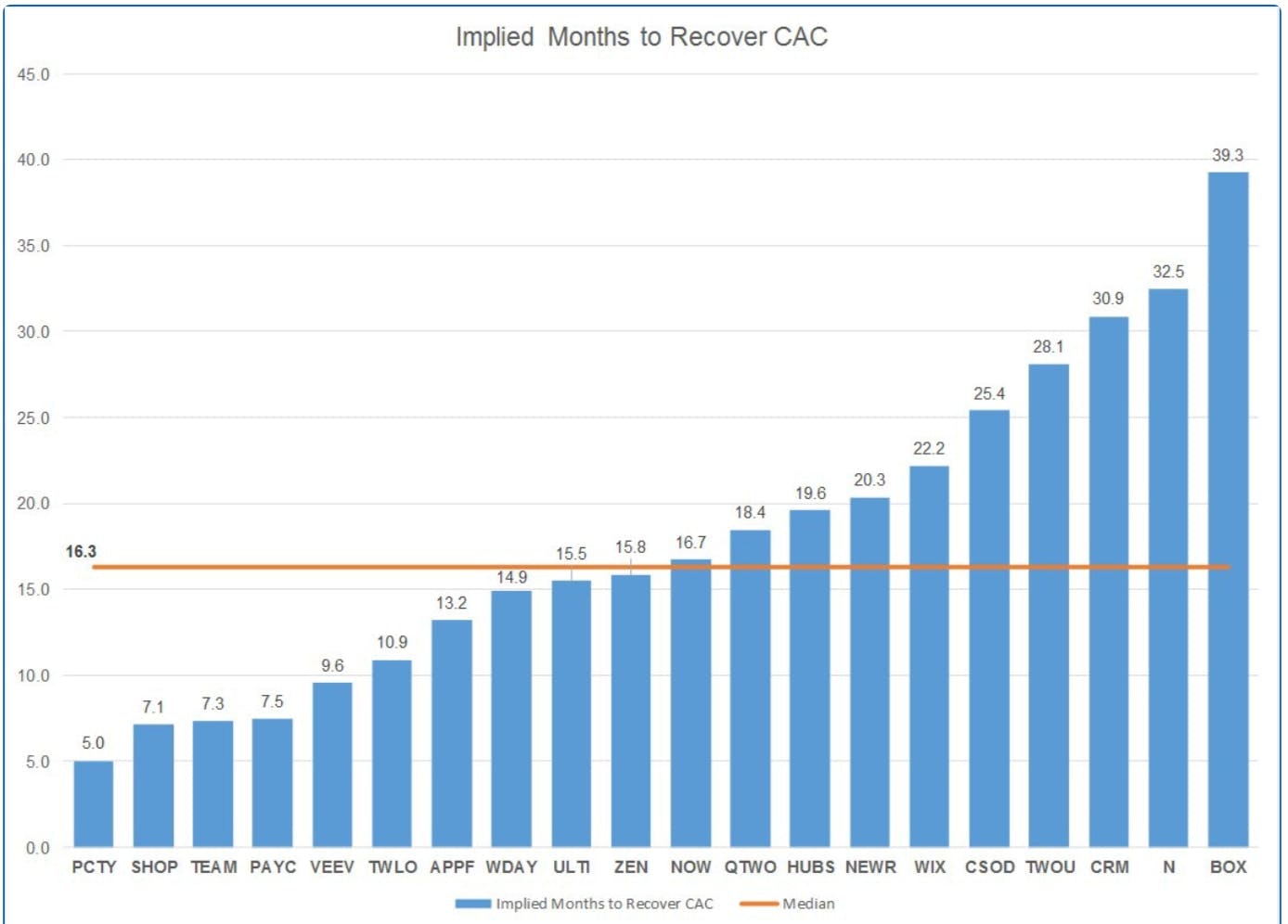

That said, there is some general agreement about what good looks like, with a target payback period of 1 years, and anything between 5-7 months considered as high-performing. However, as this study into payback periods of SaaS companies shows, there can be quite a range, with the average around 16.3 months.

Looking at the best-performing companies in this cohort gives us clues as to how they have created a low payback period.

- Paylocity: have a network of over 30,000 brokers and generate ~30%+ of their ARR through referrals.

- Shopify: acquire most customers organically (~40% by word of mouth at their IPO and 30% through partner referrals).

- Atlassian: mostly sell directly to technical users, who collaborate on product development, with a low-friction, self-serve sales model.

- Veeva: took first-mover advantage by creating a bespoke CRM for pharma and biotech reps.

The chart also illustrates how companies with a higher payback period tend to be larger (e.g Box - $771m in annual revenue, NetSuite - $200m, Salesforce - $21bn, 2U -$575m). This is logical. With bigger pockets and more predictable revenue, they can experiment with acquisition strategies, forgoing some of the efficiency that is a must for leaner SaaS businesses.

How payback period relates to other SaaS metrics

Payback period is influenced by, and influences, some familiar SaaS metrics.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

You could argue that the whole purpose of measuring payback period is to find the optimum CAC. A high CAC will worsen the payback period (as it takes longer to pay off the investment), and vice versa.

CAC Ratio

The CAC Ratio is a more visual representation of the return you’re getting on each new customer. It is shown as the percentage of the CAC paid off by the end of the expected payback period. Ideally you’re after at least 100%, with anything less meaning the customer is taking longer than average to return a profit.

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)

Though CLV and payback period are not linked mathematically, they can be seen as subsequent stages. Payback period gets you off to a good start, and then it’s over to CLV to reap the rewards. (Read more about customer lifetime value)

Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR)

Two things impact payback period; how much a new customer costs to acquire (CAC), and how much they spend. The CAC of a customer never changes (though obviously it can change from customer to customer), but how much they spend can. In other words, increase MRR, and see the payback period fall. But variables are two ways things, and if MRR starts to drop (MRR Churn), it’s going to take longer to turn your customers profitable.

Net Revenue Retention (NRR):

By including the value of upgrades, downgrades, and churn of customers within their payback period, you get a more accurate picture of actual revenue, and so a more accurate payback period reading. You can also use NRR rate as a proxy for payback period. If the NRR rate is above 100%, it should follow that your customers are becoming profitable sooner.

Four ways to reduce payback period

However you measure payback period and whatever benchmark you employ to judge success, one thing is true for all SaaS companies: reducing it is a positive. Here are four tactics that SaaS businesses can employ to reduce payback period.

1. Experiment with sales channels

The cheaper you can get customers, the faster you should get a profit from them. So it’s worth testing out new sales channels to see if you can cut the cost of acquisition. There are plenty to try. Digital tactics, like PPC, can be enabled quickly, do not require a significant upfront investment, and can be measured in real time. Others, such as SEO, traditional PR, and community creation require patience. But be careful not to analyze sales channels in terms of CAC alone. A channel with a low CAC that doesn’t produce many customers, isn’t much help. So too if the customers don’t hang around very long. So also factor in MRR, churn, and CLTV in coming up with the perfect channel mix.

2. Find the right price points

Experimenting with sales channels can take time. But changing your prices should be far easier. Clearly putting your prices up is one way to increase revenue and cut the payback period. But it’s risky too, with disgruntled customers likely to leave. It may be more palatable to change the terms of a subscription as a way to bring committed revenue in sooner. Or you could incentivize customers to pay for more of their subscription upfront.

3. Grow your base

Increasing your prices is not the only way to make more revenue from customers. Having a scaled pricing model ensures they spend more to access more of your service. Promoting technical support, training or paid-for research represent other new revenue streams. Anything that increases a customer’s spend will see their payback period reduce.

4. Cut churn

Unless you’re stripping out canceled subscriptions from your payback period calculation, then churn is going to hurt it badly. The best way to cut churn is to ensure customers don’t want to leave in the first place. And when they do, inspire them to stay by reinforcing the benefits of your product and/or offering incentives to stay.

Read our guide for more on how to calculate and reduce churn.